Chaya Ocampo Go

August 30, 2016

Disastrous #Disaster Politics

There is no such thing as a #natural disaster (see Hartman & Squires 2006).

The strongest storms and the fiercest wind speeds could be called cosmic forces of nature, yet intensifying weather conditions brought about by #climate change are linked directly to human activity. The calamities are man-made. An El Niño spell is only a disaster if it starves entire communities to desperation—and the heat turns even more tragic when those hungry are met not with food but with bullets. A super typhoon is only a disaster if it could not save over 10,000 bodies from already predicted storm surges. If early warning signs are communicated and heeded, if calamity funds are properly distributed, then storms and droughts are not disasters. The havoc wrecked by such atmospheric fury is only as catastrophic as socio-political forces allow them to harm human lives and what society values collectively.

To think and talk about disasters as ‘natural’ or ‘inevitable’ meteorological tragedies that bear no one’s fault but are the victims’ own helpless misfortunes erase the very structural injustices which predetermine people’s vulnerabilities.

Who has the power to let live and let die? Henry Giroux (2006), an American scholar of radical democracy, writes that the State is engaged in necropolitics or the #politics of death: the one who wields power is able to mark certain peoples more ‘kill-able’ than others. In his book Stormy Weather, he argues for how Hurricane Katrina which devastated the Gulf Region in the year 2005 exposed Black poverty and anti-Black racism in the United States. Race determined who is poor and who are therefore less safe, who are more vulnerable, who are to be drowned, displaced, and criminalized by the American government (see also Racing the Storm by Potter 2007). #State neglect in the ‘First World’ is now caused by the weakening of the Welfare State and the rise in privatization of government services.

To flip this case from the Global North to the Global South, State neglect in the Philippines in turn manifests as the weak capacities of a postcolonial government in the ‘Third World’. Super Typhoon #Yolanda did not only expose the bare faces of mass poverty and vulnerability among farmers and fishers, but more especially the poor coordination among national government agencies, the persistence of feudal oligarchies, and the dire lack in implementation of RA 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Reduction and Management Act of 2010 to respond effectively and efficiently to the climate crisis.

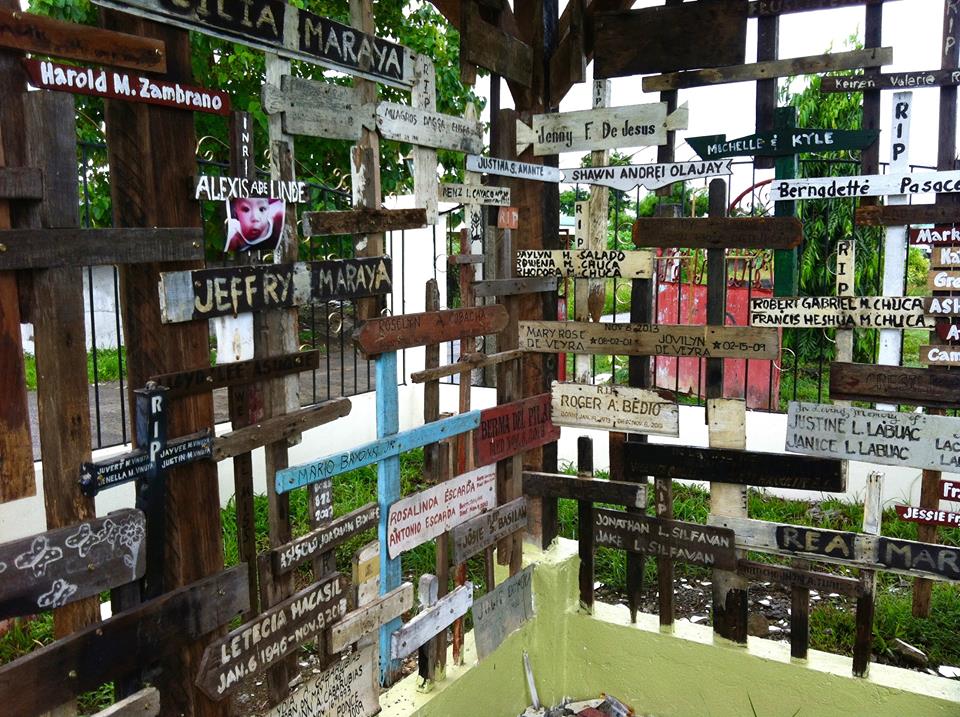

Mass grave for over 400 Yolanda victims in San Joaquin Parish, Palo, #Leyte – June 2015, photo by author

The Philippines ranks now in the world with one of the highest disaster risks, following third only to Vanuatu and Tonga. This is not only due to the archipelago’s geographic location along the Typhoon Belt or the Pacific Ring of Fire, but I argue more so because of the disastrous disaster politics continuously tearing the country into further disarray. A report entitled Disaster Upon Disaster by IBON Foundation (2015) details how the prevalence of corruption, patronage politics, and the militarization of disaster response in the immediate aftermath of Yolanda unleashed waves of disaster upon victims. Similarly, the report A Portrait of Two Storms written by Atty. Aaron Pedrosa of the Philippine Movement for #Climate Justice (Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace 2016) details cases of #disaster capitalism and the bureaucratic failures of Philippine State mechanisms. Indeed, storms are unleased everyday in the lives of living survivors.

Yolanda exposed the coloured loyalties which riddled the Aquino administration across all levels of governance: from the infamous banter between former DILG Secretary Mar Roxas and Tacloban City Mayor Martin Romualdez, down to the widespread stories of mayors and barangay captains selecting which constituents to provide relief assistance to according to their political affiliations. With the new Duterte administration’s criminalization of the poor on its ‘war on drugs’, perhaps it remains to be revealed by another super storm or quake if the president understands the more urgent need to fast-track and streamline national disaster response, to deliver the climate plan, and to address chronic poverty. The State cannot join the work to grow grassroots resilience if it continues to mark the poor for death in the ongoing rise of extrajudicial killings.

Support the Homes4Jaro Campaign

In an international forum on the state of Yolanda recovery and reconstruction held in Manila on July 2016, members of civil society organizations and people’s organizations report on the plethora of issues persisting nearly three years after. One of which is the controversial Emergency Shelter Assistance or ESA initiative, now mockingly referred to as ‘DESA’ or the ‘Delayed Shelter Assistance’. Regardless of the change in presidential administrations, the longstanding commitments of many non-government actors to sustain community-based development and monitor long-term rehabilitation plans remain.

The #CDRC joins its many partner organizations in the Disaster Risk Reduction Network (DRRNet Philippines) to pick up the double role of maintaining support for front lines disaster response (see Balik-Bayan campaign for localizing disaster response) and also advocating to national levels of government. Without this commitment by Philippine civil society to simultaneously engage both communities and the State—where development work is arguably sustained everyday activism for social and climate justice—I argue the country would plunge into deeper levels of desperation.

In partnership with Diakonie Katastrophenhilfe, CDRC has implemented a #housing project in the Municipality of #Jaro, Leyte for Yolanda survivors. To date, the donated timber to be used for reconstruction still have not been released by the Cebu Port Authority in a criminal bureaucratic delay. CDRC has already approached different government agencies: Department Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the Presidential Management Staff (PMS), the Office of the Executive Secretary (OES), the Office of Civil Defense (OCD), and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) requesting for exemption from taxes and duties and storage fees of shipments. But eight months after, the pinewood are yet to be released and the houses for the typhoon survivors still await completion.

Who has the power to let live and let die? How do living typhoon survivors turn once again into victims?

There is nothing natural with State neglect. There is no such thing as a natural disaster.

The author is a Filipina scholar at York University and a Research Fellow for the Citizens’ Disaster Response Center. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of CDRC.

—

Resources:

Giroux, H. (2006). Stormy Weather: Katrina and the Politics of Disposability. Colorado:

Paradigm Publishers.

Hartman, C., & Squires, G. (Eds.). (2006). There Is No Such Thing As A Natural Disaster: Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina. New York & London: Routledge.

IBON Foundation, Inc. (2015). Disaster Upon Disaster: Lessons Beyond Yolanda. Quezon City: IBON Foundation, Inc.

Pedrosa, A.M. (2016). A Portrait of Two Storms: The State of Yolanda Reconstruction Two Years After. Manila: Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace / Caritas Canada

Potter, L. (2007). Racing the Storm: Racial Implications and Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

Leave a Reply